|

|

|

Memoirs of a Working Musician

| |

Music plays an important part in all our lives. It's an important source of entertainment and enjoyment in concert halls, nightclubs and radio programming. But it also serves other purposes. Without music, television and movies would not be nearly as enjoyable or as effective. An excellent example of the effectiveness of music in film is the shower scene in the movie "Psycho." There is no dialogue, only music from Bernard Herrmann's wonderful score. Try watching the scene with the sound turned off. The scene significantly loses its impact. Music is with us throughout our day. We tend to take it for granted because we hear it everywhere we go, playing in the background in elevators, restaurants, shopping malls, supermarkets and health clubs, to name a few. Without music our lives would be quite dreary.

|

| |

Music as a profession is generally misunderstood by most people, who think of it as unattainable by the average person on the one hand, or as a hobby or second job on the other. In general, people think that all musicians fall into one of two categories. There is the gifted artist, who might be a classical soloist, such as the brilliant cellist Yo Yo Ma; or a jazz artist, such as the great trumpeter Wynton Marsalis; or a big rock star, such as the late Elvis Presley. All other musicians are generally thought of as being hobbiests or part-time players, such as the friend or family member who plays an instrument to entertain at a party, or the guys playing in the band at a wedding. On numerous occasions people have said to me, "You sound pretty good. What do you do on your regular job?" Most people seem to be totally unaware of the fact that there are many "working stiff" musicians who never become stars in their own right, but nevertheless manage to make a living playing a musical instrument.

|

| |

When I first became interested in music as a profession I received much encouragement from my parents, my music teachers, and from working musicians. I was led to believe that because of my talent and dedication I had a chance of "making it" in the music profession. The situation was very similar to team athletics. A player shows promise and is encouraged to pursue a profession in which only a very small fraction of the people who dream of "making it" actually do. And just like in sports, the "minor league" players get overlooked by the general public; the "stars" receive all of the attention (and money!). The story I'm telling here is the account of someone who has worked his whole adult life as a musician, never working a day at any other job. And while never attaining real "star" status or making a fortune in the process, I've managed to make a decent living at it for over thirty-seven years.

|

Part One: Beginnings

|

The way I got my start in music is a classic story, right out of "Music Man". The year was 1956, I was 10 years old and in the 4th grade. My family is originally from Texas, but at that time we were living in Sydney, a little farming community in western Nebraska. My Dad was party chief on a "doodlebug" crew, in oil exploration. I had been exposed to some good music--my parents had a few jazz and light classical records, standard fare--Benny Goodman, Louis Armstrong, Glen Miller, the "Grand Canyon Suite" by Grofé, "Rhapsody in Blue" by Gershwin. I played those records a lot, and the music spoke to me. I watched the Lawrence Welk Show on TV every week. I remember Big Tiny Little playing honky-tonk piano; Myren Floren on accordion, wearing that legendary big smile; Pete Fountain, with his bald head and goatee, playing New Orleans dixieland clarinet; and all those shiny saxophones right in the front row.

|

| |

One day a salesman came to my school and set up several band instrument display cases in the gym. We kids were brought in to see if any of the instruments struck our fancy. There were instruments of all shapes and sizes, from flutes and clarinets to trumpets and trombones. At first I wanted to play the trumpet; maybe I'd be the next Harry James. But the school band director took a look at my chops and told me that I had too much of an overbite to play the trumpet. He said I was physically more suited for some kind of reed instrument. Then I saw it, what was undoubtedly the most beautiful thing I'd ever seen up close--a tenor saxophone! Well, my parents took one look at the price tag and nixed that idea. No way were they going to shell out that kind of dough on something that sonny boy might end up throwing in the corner two weeks later. So the salesman suggested a clarinet--inexpensive, lightweight and easy to carry, and I could always get a saxophone later, if I proved to be musically inclined and serious enough about it. He said that all good saxophone players "double" on clarinet, anyway. My folks went for it, and my mother drove into Fort Worth to get me a nice wood clarinet. I was on my way to making musical history (in my mind, anyway).

|

| |

I fell in love with that horn. I was quiet and shy as a child, and didn't make friends easily. Playing the clarinet was an escape for me. I threw myself into it. I must have driven my folks half crazy practicing the thing, but the practice payed off and I got quite good. At that time we were moving around a lot, never staying in one place for more than two or three months. Every time we moved and I changed schools, I'd be placed in the last chair of the clarinet section, and I'd have to start working my way up. By the time I'd get up close to first chair we'd move again, and I'd have to start all over at the bottom rung of the ladder. It was pretty frustrating, but I think it was good for me, because I never got a chance to make it to the top and then get complacent. I always had to stay on my toes.

|

| |

The summer before I entered junior high my mother finally put her foot down and said "no more" to the road life. My dad dutifully complied. I think he was pretty road weary himself. We settled down in Fort Worth, Texas. Dad got a gig as a geophysicist in the oil company's home office. As it turned out, he went from being on the road to commuting, driving to and from Dallas five days a week.

|

| |

Monnig Jr. High School on Ft. Worth's west side had a sizable marching band. Since we were no longer moving around, I now had the chance to make it as top dog in the clarinet section. Competition was fierce, but I quickly moved up to first chair. Then the band director started talking up the idea of forming a jazz big band, and he wanted to make me his lead alto sax player! There were a few snags, however. I had never even touched a sax before, and I didn't know if the folks would be into springing for a horn. Well, my mother, being my biggest fan, went to bat for me and convinced my dad to cut loose of the bread for a used alto. We got it pretty cheap; it was in sad shape. The high e-flat key was broken off, among other things. But I learned to play the thing really fast. That instrument dealer in Nebraska had been right. Starting on clarinet made taking up the saxophone a snap.

|

| |

Playing jazz was a whole new ball game. It seemed to take forever for me to learn how to swing. I remember practicing my part on an arrangement of "Stardust" about a thousand times. I really don't know how my parents stood it. My mother tried to help. She'd sing the melody to me, trying to get me to pick it up by ear. I pulled out those old jazz records and started studying them, learning the solos note-for-note, playing along and trying to cop the phrasing. The swing feel finally came to me. Now I needed to learn to improvise. I learned jazz harmony, banging out chords on the spinnet piano that my folks had bought for my sister Becky. I swear I spent more time on that piano, plunking out jazz chords, than she ever did practicing her classical lessons. She eventually moved on to the flute, which she still plays. But back to my story. I was determinded to learn to improvise. I had developed a good ear by copying melodies and chords, as well as solos, from records. But I couldn't make up my own melodies, which is really what improvising is all about.

|

| |

Then one day it happened. It all just fell into place. I understood the whole process--how the melody fit with the chords, and how to make up my own melody that would fit over those same chords. But I needed to hear more players. I'd really only been exposed to Swing Era musicians up to that time. I wanted to know what the current guys were doing. I got the soundtrack to the TV show "Peter Gunn", by Henry Mancini that year as a Christmas gift. There were some great LA jazz players on that album--the Condoli brothers on trumpets, Dick Nash on trombone and brother Ted on alto, among them. I transcribed all of the sax solos off that album and was anxious to hear more players. I talked my mother into taking me to the record store across from the TCU campus to buy me five new jazz albums. Neither of us knew what to buy, so we asked the store owner to recommend some albums. It turns out that the owner was Sumter Bruton, the father of Steven Bruton, guitarist with Bonnie Raitt. The albums that Sumter picked out changed my life forever. They were: "Time Out" by Dave Brubeck, with Paul Desmond on alto; "Moment of Truth" by the Gerald Wilson big band, with Harold Land and Teddy Edwards on tenor saxes; "Art Pepper Meets the Rhythm Section" with Pepper on alto, Red Garland on piano, Paul Chambers on bass and "Philly" Joe Jones on drums (Miles Davis' rhythm section at the time of the recording); "The Bridge" by Sonny Rollins; and the capper, the one that made the biggest impression, "Jazz Track" by Miles Davis. Side one featured Miles with a French rhythm section, playing the music from a French film entitled "From the Elevator to the Scaffold". But side two was something else, with Bill Evans on piano, the afore-mentioned Paul Chambers and "Philly" Joe Jones on bass and drums, and featuring Julian "Cannonball" Adderley on alto and John Coltrane on tenor. When I heard those two cats, I was hooked. My life was never the same. I had never heard anything like what these guys were playing! Cannonball played so sweet and smooth, and 'Trane! I'd never heard such yearning, such searching, such a need to get the notes out that they seemed to tumble out of the horn, one on top of the other. I began to collect every album I could find that had Miles, Cannonball and/or Trane on them.

|

| |

At about this same time I began to play professionally in rhythm 'n blues bands in local Ft. Worth dives, places I'd be scared to go into now. But I was young (15!) and naive. I guess people thought that I was cute, because they left me alone. By this time I'd acquired an old Conn tenor and the same Berg Larson mouthpiece that I still use today, becoming primarily a tenor player. I got turned on to Ray Charles records, featuring David "Fathead" Newman (a Dallas native) and Hank Crawford. Those two guys became major influences on my playing style. Not only could they swing and play over changes, but they were soulful players to the extreme. Now I don't mean to insinuate that Cannon and Trane weren't soulful players. Of course they were two of the most soulful players ever to pick up a saxophone. But Hank and Fathead were coming from a different place. While both players were polished and refined, their playing seemed to come more from the street.

|

| |

So those were my major influences: John Coltrane, Cannonball Adderley, Fathead Newman and Hank Crawford--in that order. There were many others, including the previously mentioned Harold Land, Teddy Edwards, Sonny Rollins, Art Pepper and Paul Desmond. I played "Take Five" in a talent contest called "Stairway to the Stars" at Casa Manana, a dinner theater in Ft. Worth. I should also list Sonny Stitt, Gene Ammons and Stanley Turrentine. Several of the "Texas Tenors" were also influential, including Fathead, King Curtis, Clifford Scott (who recorded the legendary record "Honky Tonk" with Bill Doggett), James Clay (I got to work with him a few times in casual bands in the Ft. Worth-Dallas area), and a local tenor player named Billy Tom Robinson.

|

| |

Billy Tom was an amazing player. I met him in a local dive called the Cellar, sort of a beatnick joint where the fine, upstanding citizens of Ft. Worth went "slumming". Billy Tom had an old beat-up horn that was held together with rubber bands and chewing gum. He got a terrible sound out of the thing, but played great ideas! He taught me so much. He could mutter a few words that would make such a huge difference in my approach. One day he asked me, "You hip to the Scottish scale, man?" I said, "No, I've never heard of it." So he played the scale for me. What he played was the pentatonic (five-note) scale, which is extremely important in jazz and contemporary music, as well as pop music. Most pop melodies are based on some form of the pentatonic scale. Billy Tom helped me in many areas of playing the saxophone. He taught me how to breathe and how to leave space. He told me that it wasn't always necessary to play a ton of notes. I don't know if he ever knew how important his little hints and suggestions were to my developement as a player. Around that same time I was taking private saxophone lessons, but I learned much more standing next to Billy Tom on the bandstand night after night.

|

| |

I attended high school at Arlington Heights High School, also on Ft. Worth's west side. During my sophomore year I played lead alto in the jazz big band, which we called the "Lab Band", like the legendary bands at North Texas State, which was in Denton, just 35 miles to the north. By my junior year I was directing our "Lab Band", writing charts for it and playing the tenor solos.

|

| |

Ft. Worth was not exactly a haven for jazz musicians, but in '62 I got to hear some name players. Maynard Ferguson's band gave a concert at TCU. The band that he had at that time was the best one he ever put together, in my opinion. His sax section at the time was Lanny Morgan on lead alto, Willie Maiden and Frank Vicari on tenors and Ronnie Cuber on bari. All four of those guys were brilliant players.

|

| |

There was a jazz concert series that year at the Texas Hotel downtown. My parents bought us tickets to the entire series. We heard The Brubeck Quartet, with Paul Desmond on alto. Among other bands in the series were George Shearing and Jack Teagarden. But the band that impressed me the most was Stan Kenton's Neophonic Orchestra. He had just added mellophoniums, which were sort of like french horns with the bells straightened out, so that they faced forward, like a trumpet. So the instrumentation was: five trumpets, five trombones, five saxes (alto, two tenors and two baris, one of which doubled on bass sax), five mellophoniums, bass, drums, and Kenton on piano. It was the most powerful band I'd ever heard! The lead alto player was Gabe Baltazar, who was an absolute monster! When I later learned that Kenton was putting on a two-week jazz clinic at a small college in Denver, I convinced my parents to let me go, my first trip on my own away from home. I took the train all by myself all the way from Ft. Worth to Denver. What a wonderful experience that was! I played in a big band led by alto saxophonist Charlie Mariano, and attended an arranging class conducted by the great composer/arranger Johnny Richards. Joel Kaye, a member of Kenton's sax section, gave a lecture on the art of saxophone playing. He talked about picking out reeds and mouthpieces, and gave us suggestions as to how to get the most out of practice sessions. I was able to make a great leap forward in my development as a result of the Kenton Clinic experience.

|

| |

In my senior year I won an "oustanding musician" award at the Brownwood Stage Band Contest, in which 48 bands competed, and at which Leon Breeden, then director of the North Texas Lab Bands, was a judge. I had already decided that NTSU was where I wanted to attend college. The school had (and still has) a reputation for turning out great jazz players. Several of the Kenton band memebers were NTSU almni, including trumpter Marv Stamm and drummer/trombonist Dee Barton. Breeden recruited me on the spot, and upon graduation from high school I applied to and was accepted at North Texas State (now called the University of North Texas).

|

| |

In my first semester at NTSU, after lab band auditions, I was placed in the Three O'clock Band on second tenor, making me the number six tenor player in the school. To give you an idea of what the competion was like at that time, Billy Harper (who later played with Thad Jones/Mel Lewis and Art Blakey, among others, as well as being a concert and recording artist in his own right) was the number one tenor player in the school, playing the jazz tenor chair in the One O'clock Band. I moved up to jazz tenor in the Two O'clock Band in the spring semester, making me number three.

|

| |

It seemed that I was well on my way to the top again, just like in the past. But I was a really poor college student. Other interests were getting in the way. I was still playing with R 'n B bands in bars in the Dallas-Ft. Worth area, but by this time I was working six nights a week. I had also discovered women. I learned that being a musician gave me an advantage in that area. I really was not able to focus on school, and I flunked out. I got an offer to join an R 'n B band led by fellow Ft. Worth native Arlan Harmon. The band was based in Los Angeles. I flew out to L.A. with a trumpet player friend from high school named Bobby Blood. It was my first time on a plane. I remember my dad telling me not worry if the wings flapped a little, that it was normal.

|

| |

We really scuffled out there in L.A. I had become engaged before I left home, and to complicate matters, I flew back to Ft. Worth on a night off and married my first wife, Linda, bringing her back to L.A. with me. I was back at work the very next night. I didn't even take an extra day off to get married--I couldn't afford it. The band played in the L.A. area for a while, went on an ill-fated trip to Mexico City (I could write a another whole story about that fiasco!), and then worked our way up the Pacific coast. We spent some time in the San Francisco area, then six months in Portland and six months in Seattle. By this time my wife Linda had become pregnant, and my oldest son Chad was born in Seattle. So here I was, trying to make a living out on the road, with a young wife and child in tow.

|

| |

The year was 1967, the year that Trane died. On nights off we frequented a jazz club in Seattle called the Penthouse (where the Coltrane "Live in Seattle" album was recorded). I got to hear some jazz greats--Oscar Peterson, Roland Kirk, Cannonball Adderley and the legendary Miles Davis. I got to meet Cannonball and his band. I remember Joe Zawinul exclaiming "Mini Mama!" upon seeing my then very pregnant wife in a mini dress. That was the title of one of Joe's tunes that the band was playing at the time. We got to hang out with Nat for a little while and found him to be a very charming, gracious and informative man. Cannon's band was seriously smoking! In my opinion, he was one of the most underrated saxophone players of all time. Roland Kirk was also very impressive. I had taught myself to play two horns at once during a period when our band was without a trumpet player, but Roland played three saxophones at the same time--a one-man sax section! And he was no carnival side-show act. He could really play.

|

| |

Then there was Miles. At that time his band consisted of Herbie Hancock on piano, Tony Willians on drums, Buster Williams on bass (regular bassist Ron Carter didn't make West Coast trips back then) and Wayne Shorter on tenor. They were playing some of the old standards--"Four", "Bye Bye Blackbird", "If I Were a Bell", etc. They'd play the head and then I'd get lost. I couldn't seem to follow the changes during solos. It wasn't till years later that I discovered, on the "Plugged Nickel" album from that same period, that they were throwing out the changes and playing "free-form" during the solos. At the time, though, I didn't know what they were doing, but I was digging it, just the same.

|

| |

News of Trane's death came as a real shock. I was devastated. His playing, his dedication and his spirituality had been such an inspiration to me. He was "The Cat" on tenor, in my opinion. Regretably, I never got to hear him play in person. I had missed an opportunity to hear him a few months before he died, when he recorded the "Live in Seattle" album. I was in Portland and would have driven up to Seattle to hear him, had I known that he was appearing there. I wondered who would be declared his successor. Sonny Rollins immediately came to mind. Rollins was scheduled to appear at the Penthouse the very next week and I couldn't wait to hear what he had to say on his horn. Well, Rollins cancelled that gig and no one saw him for at least a year after Trane's death, according to Downbeat Magazine, my most important source of news in the jazz world. It was as if Rollins was saying, "I don't want the gig" of succeeding Trane as top dog on tenor. But Trane left a legacy that will live on forever. I truly believe, as many do, that John Coltrane was a prophet.

|

| |

After the Seattle stint our band tried working on the East Coast for awhile, but it got to be too tough having a family on the road, and I wanted to continue my education, so I moved my family back to Texas and went back to NTSU.

|

| |

After auditions in the spring semester of 1968 I was placed on jazz tenor in the Five O'clock Band, once again having to start at (or near) the bottom and work my way back up. Although I was still playing R 'n B six nights a week in Dallas, I was able to focus on school much more than I'd been able to the first time out, and my grades improved drastically. I made it back to jazz tenor in the Two O'clock Band in the fall, and finally made the jazz tenor chair in the One O'clock Band in the spring of 1969. I was in excellent company--Dean Parks (L.A. session guitarist/composer/producer) was playing lead alto, Tom Malone (Saturday Night Live band, the Blues Brothers) was on lead trombone, Jeff Sturges (composer for tv shows "Simon & Simon", "Murder, She Wrote", etc.) was also in the trombone section, Matt Betton (long-time Jimmy Buffet sideman) was on drums. My time at NTSU was extremely valuable to me. I was really able to work on refining my sound, getting my reading chops together and learning more about jazz theory, improvisation and big band arranging. The personal contacts that I made there were also extremely valuable. NTSU Lab Band alumni are a like brotherhood. I made some close friends during that time, many of whom are still my friends today.

|

Part Two: The Middle Years

|

In early 1970 I was approached by singer Jerry Fisher about being musical director of a new band that he was putting together in Dallas. The pressures of making a living while attending college were getting pretty heavy, and I saw an opportunity to "make it" in the pop music scene. Jerry was a wonderful, soulful singer, strongly influenced by Ray Charles. I put the band together for him, recruiting players mostly out of NTSU. The great trombonist Steve Turré was among the members. The band's instrumentation was: guitar, keyboards, bass, drums, and four horns (trumpet, two tenor saxes and trombone), and Fisher, of course, on vocals. I wrote most of the arrangements, and even wrote a couple of songs for Jerry. We worked mostly in the Dallas area, with occasional trips to Oklahoma (Fisher's home state), and we spent a month in Lake Tahoe.

|

| |

While we were in Tahoe Jerry and I flew to L.A. to play our demo for composer/arranger/producer Mike Post, whom Jerry had met somewhere. After hearing the demo, Post said that we sounded too much like Blood, Sweat and Tears. I gave him several reasons why we didn't sound like BS&T, but he said that audiences weren't hip to all the subtleties that I was talking about. He said that they'd hear a band with a lot of horns and a white singer who sounded like Ray Charles and they'd think "Blood, Sweat and Tears." After that I became pretty discouraged about the band ever making it big. I'd left school to put the band together, and it seemed that it wasn't going anywhere. By this time Jerry had bought a nightclub in Dallas, so the band had a permanent gig, but there didn't seem to be any future in it. Besides that, I wasn't getting along with the drummer. He and I had artistic differences. One night we almost came to blows. Jerry's solution was to reorganize the band, firing the horn section (which had been cut down to two players--myself and trumpeter Fletch Wiley), adding a female vocalist and keeping the drummer (who joined Sonny and Cher's band about a month later).

|

| |

Shortly after being fired from Fisher's band my marriage with Linda ended. I imagine that I was pretty hard to live with at the time, but I was completely devastated when Linda told me that she wanted to start seeing other guys. She told me that she was planning to take a trip to New York to see a guy she'd met while waitressing at Fisher's club, and I moved out of the house. Losing my wife also meant losing my son, except for occasional visits. My son Chad was 4 years old. No longer would I see him on a regular basis. I was despondant, at the lowest point in my life. I needed to get away, to clear my head, and to try and get a new outlook on things.

|

| |

I was offered a gig with the Third Avenue Blues Band, a great R 'n B band based in Oklahoma City. I toured with them for about a year. During that time we spent about six months in the Boston area, where I got to hear Herbie Hancock's band at the Jazz Workshop. At that time Herbie had Benny Maupin playing with him on soprano and tenor saxes and alto flute. I was very much impressed by the band and by Maupin's playing. Herbie had matured considerably since I had seen him with Miles in '67, when he was still a kid, barely out of high school. Later that year our band spent a month in Vegas, playing the "Pussycat a Go Go", which was an afterhours hangout for locals working the "strip". We worked the "graveyard" shift--midnight to eight am! After leaving Third Avenue I went back to Dallas and married Lynde, my second wife.

|

| |

In '72 I was offered a road gig playing lead alto with "Mr. Blue Eyed Soul", Wayne Cochran and the C.C. Riders. The band literally lived on the road, working year-round, with a week off for Christmas. There were players on the band that didn't even have an apartment. They'd just go visit their parents during the holidays. Some of the guys had been on the band for seven years! We travelled in a forty-passenger bus with a bathroom in the back. It was nothing like the fancy tour buses of today, with their lounges, tv's, vcr's, cd players, microwaves and bunks. Each guy in the band got two seats. We had to stretch our legs across the aisle, resting our feet on the armrest of the seat across from ours. When we needed to go to the bathroom we'd have to climb over guys' legs while trying not to disturb them. I didn't sleep for the first two weeks, which gave me the opportunity to memorize my part, since Wayne wouldn't let me use a music stand, saying that it would detract from the show. I couldn't read the music from the floor, so I had to memorize my part. While everyone else was sleeping, I was listening to a tape of the show, playing "air saxophone", fingering the notes on a phantom horn. While playing the show, I also had to try to pick up the dance steps that the other guys were doing. I'd never really been much of a showman, but everyone became a showman while working with Wayne Cochran!

|

| |

Life on the road with Cochran was pretty rough. My starting salary was $200 a week and I had to pay for my own room, which I shared with another band member. We often travelled a thousand miles between gigs, sometimes going two or three days without checking into a hotel, which saved us money on rooms, at least, but sometimes made us a pretty ripe smelling group, since we didn't have access to showers for two or three days running. We once went from Houston, Texas to Utica, New York in thirty-six hours. We left Houston after the gig on a Sunday night and arrived in Utica at five in the afternoon the following Tuesday, and played two shows that night!

|

| |

Even though conditions were practically unbearable, playing on Wayne's band was a wonderful musical experience for me. That band was probably the most high energy band that I've ever played with. During my stint with Cochran I met bass legend Jaco Pastorius. He and I roomed together briefly when he first joined the band. What can I say about Jaco that hasn't already been said? He was truly phenomenal, and at that time he was only 19! One night while we were in Boston Jaco and I went to see Chick Corea and the Return to Forever band, with Airto on drums, Flora Purim on vocals and percussion, Joe Farrell on tenor sax and flute, and Stanley Clark on bass. After the set Jaco said to me, "I like what Stanley's doin' on upright, but he ain't showin' me nothin' on electric!" Jaco was a brash kid, but the thing is that he could back it up. His death as the result of his alcohol and drug use was a real tragedy. When I knew him he didn't drink and he wouldn't touch drugs. He had a young wife and child, who he loved dearly. He lost everything because of his addiction, including his life.

|

| |

I worked with Wayne Cochran for about six months, during which time my son Lonzo was born. For a short time, wife Lynde and son Lonzo traveled with me on the bus with the Cochran band. I think Lynde still has a picture of Jaco standing in the aisle of the bus playing bass, while then two-month-old Lonzo is lying in his crib wearing headphones, listening to Jaco wail! But conditions on the road were impossible for my family and me. I left the band and took my family back to Dallas. I worked clubs and casuals around town, did some studio work, and even played a couple of shows with "The King", that's right, Elvis Presley! I'd never been an Elvis fan, but being on stage with him was quite a rush. He was undoubtedly the most charismatic performer I've ever worked with.

|

| |

In '73 I got a call from fellow NTSU alumni Jeff Sturges, whose band, the Universe, was backing up Tom Jones for a six month American tour. Conditions were quite a bit better than the Cochran gig. We flew on a chartered jet, stayed in nicer hotels, and, most importantly, got paid almost double what I was making with Wayne. But the gig was a snore for me musically. I mean, how many times can you play "What's New, Pussycat" or "Delilah" without wanting to jump right out of your own skin!

|

| |

After being on the tour for two months I heard about a band that was being put together by New Orleans singer Luther Kent. The horn section was mostly Wayne Cochran alumni, and they asked me if I'd be interested. I jumped at the chance to play some real music again, and I moved my family to Baton Rouge, where the band was forming. After rehearsing and playing a few gigs in Baton Rouge, we went into a studio and made a demo with the intention of trying to get a record deal. In the mean time, in order to survive, we got a gig in New Orleans, at the Ivanhoe, a club on Bourbon Street, right in heart of the French Quarter.

|

| |

Luther was (and still is!) one of the greatest singers I've ever worked with, and the band was one of the most soulful bands I've ever had the pleasure to play with. But when Luther couldn't get out of an exclusive contract with producer Lou Adler, the band broke up. Trumpeter Marshall Cyr, formerly with Edgar Winter's White Trash, suggested that he and I put a new band together in order to keep working. We both had families and needed to keep the money coming in. We named the band "Sugar Daddy" and kept the Ivanhoe gig for another two years. We worked six nights a week, six shows a night on weeknights, and seven shows on weekends. The gig started at 11 pm and ended at 5 or 6 in the morning.

|

| |

New Orleans was a great experience for me musically. I really learned how to play the blues in New Orleans. I did studio work for the great producer/songwriter/arranger Allen Toussaint, playing on albums by the likes of John Mayall, James Cotton and the vocal group LaBelle (Patti LaBelle, Nona Hendricks and Sarah Dash). That's me playing tenor on the instrumental interlude on "Lady Marmalade", a number one hit for LaBelle. I learned a lot from Toussaint about arranging for horns. He taught me a lot about using space, and that sometimes what you leave out is more important than what you put into a horn arrangement. I also performed with many local legends of R 'n B as a result of my association with Toussaint, including Dr. John, Irma Thomas, Ernie K-Doe, and the legendary pianist Professor Longhair.

|

| |

In New Orleans I finally got to play some jazz gigs. Up to that point, most all of the work that I'd done had been with R 'n B bands. Don't get me wrong. I love R 'n B, and I've got R 'n B roots that go back a long way. But jazz is my first love, and getting to play jazz gigs was extremely rewarding to me. I led my own quartet, playing jazz clubs in the New Orleans area. I even got to share the bill with one of my idols, Fathead Newman, one night at a posh uptown jazz club called Rosie's (Fathead got top billing, of course). During my years in New Orleans I had the privelege to work with several local legends of jazz, including Ellis Marsalis, Harold Baptiste and James Black. I also became involved in jazz education while living there, teaching saxophone and improvisation at the University of New Orleans, and playing in their jazz band. I also taught privately in my apartment, which, oddly enough, had at one time been the local Musician's Union. All in all my time in New Orleans was one of the most productive periods in my musical life.

|

| |

One of the many bands I worked with while living in New Orleans was a really strange group of players. The nucleus of the band was: Angelle Trosclair, a wonderful jazz singer and pianist; John Vidacovich, undoubtedly the most musical drummer I've ever worked with; rock guitarist/singer Billy Gregory, formerly of L.A. rock band It's a Beautiful Day; and myself. We had an afterhours gig at a place on Decatur Street in the French Quarter called Gino's Back Room. Gino was a great music fan and gave us complete artistic freedom. All he asked was that I occasionally play Bill Doggett's "Honky Tonk" for him. He loved that tune! I obliged, but I'd only play it once a month. I told him that the song would get stale if I played it more often than that. He bought it, and didn't press me on it, unless he got really juiced. The music that we came up with in that band was a strange blend of rock and jazz unlike any "fusion" music that is usually the result of such a marriage of styles.

|

| |

In New Orleans I had finally made a name for myself. People recognized me on the street and I was somewhat of a star. But I was a medium-sized fish in a little pond, and besides, many of the local musicians didn't accept me, because I wasn't born there and I wasn't black. New Orleans is sort of a self-contained city musically. The local players can be downright snobbish. It's next to impossible for an outsider to become accepted by the locals. The weird thing is that it's not the audiences that have that attitude so much as the players. I always felt accepted by the audiences. I'd never been on the receiving end of any kind of discrimination before living in New Orleans.

|

| |

I certainly knew about discrimination first-hand. Being a white guy from Texas, I saw black people being discriminated against. I remember "colored" restrooms and water fountains when I was a child. I remember "colored" people having to ride in the back of buses. My grandparents were downright bigots, and my parents, while not nearly as bigoted as my grandparents, were not exactly "bleeding heart liberals" either. My generation grew up during the civil rights struggle. Those of us who had any intelligence were determined to do away with discrimination once and for all. I'd certainly never experienced reverse discrimination. I had played a few gigs in black clubs in the Dallas-Ft. Worth area and had always been accepted by black players and audiences, once they heard me play. After all, all four of the players that I listed as being my biggest influences were black. But in New Orleans I got the message loud and clear: "If you're not black and from here, you ain't really sayin' nothin'!" I needed to move on.

|

| |

I checked out New York. My parents, as well as ex-wife Linda and eldest son Chad, were living there at the time, so I took the opportunity to visit family and at the same time check out the music scene. Lou Marini (Saturday Night Live Band, the Blues Brothers), a friend from NTSU, took me around and introduced me to some of the N.Y. players, one of whom was Michael Brecker. Lou promised to give me his throw-away gigs if I decided to move there, but as it turned out, I ended up moving to Los Angeles instead.

|

| |

In '76 my marriage with Lynde ended, and my new girlfriend Beth, soon to be wife number three, had been a Playboy bunny in L.A., and still knew a lot of people out there. She felt confident that she could find work and, as luck would have it, an opportunity arose for me to get out there and make some contacts. Angelle landed an album deal with Epic Records and we went out to L.A. to make the record. The music industry was booming at the time, and we had a big budget to work with. We used practically every name session player we could think of. We had Alfonso Johnson on bass, Russ Kunkle on drums, Joe Sample, Victor Feldman and Dave Grusin on keyboards, Snooky Young on lead trumpet and Bill Perkins on baritone sax, to name a few. Victor asked me to audition for the L.A. Express, who were looking for a sax player. They liked my playing and wanted me to fill the spot, but they didn't really have anything to offer at the time. They were just playing a few gigs around the L.A. area. By the time I got it together to move out there the band had broken up.

|

| |

Angelle's album didn't do too well. (My mother bought about twenty copies and bugged the record dealers in New York about ordering more, which, of course, they didn't do.) The label had tried to turn Angelle into a pop singer. She had the looks. She was an attractive woman, and a natural blond, which was almost unheard of, especially in L.A., the home of bottle-blonds. The resulting album, while having a few nice moments, was too watered-down to be marketed as jazz, and too jazzy to be marketed as pop. But it was that album that got us out to L.A.

|

Part Three: The LA Years

|

Beth and I moved to Los Angeles in August of 1977. Angelle had preceded us by a few months and we stayed with her until we could get a place of our own. At the time we didn't even own a car. We hadn't needed one in New Orleans, going everywhere we needed to go by walking or by taking a streetcar or a cab. But now that we were living in LA transportation was a major concern. LA is not a good town to live in if you don't own a car. We needed to be as centrally located as possible. We got an apartment right on Sunset Boulevard, across from the Comedy Store. The building we were living in is now the Mondrian Hotel. Beth got a gig bartending at the Playboy Club, going to work by bus, and I scuffled hard. I got practically no work that whole year. I played a tenor solo on an album for REO Speedwagon, "You Can Tune a Piano, But You Can't Tuna Fish". I went on a few auditions, but didn't get the gigs. I played a couple of gigs with Angelle, one of which was opening for Stanley Turrentine in a jazz club in San Francisco. I got a kick out of that! I'd always really admired his playing. I made a solo demo and Angelle's manager shopped it for me, but no label was interested. To complicate matters further, Beth had become pregnant. Things were looking pretty bleak, as far as my making a living in L.A. was concerned.

|

| |

Later that year I hooked up with some New Orleans ex-patriots who were working at a place in Topanga canyon called the Corral. Ex-New Orleans singer/piano player Eddie Zip had a big horn band that played there on a weekly basis. There was virtually no bread, but at least I was playing and meeting some other players. That was the way it was (and still is!) in LA--you had to take gigs for lame bread just to keep your chops in shape, to get heard and to meet other players, as well as band leaders, record producers, etc. This was tough for me to take, because I had reached a level in New Orleans where I wouldn't leave my house for less than a hundred bucks, and now I had to take gigs that paid ten dollars or less!

|

| |

In the summer of '78, a month after my daughter Lauren was born, I went to Europe with New Orleans singer/pianist icon Professor Longhair. We played the summer jazz festival circuit--two weeks at the Grande Parade du Jazz in Nice and three days at the North Sea Jazz Festival in the Hague in the Netherlands, as well as a few dates in Norway and Sweden. I was amazed at how much more receptive European audiences were than American audiences. There was so much more respect for players and music in general over there than there was in the U.S. I could certainly understand why so many American jazz players had moved over there.

|

| |

The trip was a great experience for me. I fell in love with France, and hoped that someday I'd get a chance to go back there. In Nice I got to hear some of the legends of jazz, including Stan Getz, Dizzy Gillespie ( I sat in with him on one of his sets), Eddie "Lockjaw" Davis, the Buddy Rich band, and an all-star band fronted by Lionel Hampton, with too many jazz greats too mention here. Fathead Newman and Hank Crawford were playing sets together. That was a real treat for me. Here were two of my biggest influences, sharing the stage. One day alto sax legend Eddie "Cleanhead" Vinson sat in with them and I swear he cleaned both of their clocks! I got to meet Cleanhead when he came and sat in with Professor Longhair. I knew that Trane had played with Cleanhead, so asked him about it. I said, "I understand that Trane used to play in your band". " That's right", Cleanhead replied. "I'm the cat responsible for makin' Trane a tenor player. When he joined my band he was blowin' alto. I heard him play, and I told him, 'Ain't nobody plays as good as you gonna play alto in my band!", and the rest, as they say, is history.

|

| |

Back in LA, my Corral gig with Eddie Zip led to my connecting with fellow Ft. Worth native singer/songwriter/pianist Glen Clark (now playing with Bonnie Raitt), who was playing at a club in Calabasas called the Sundance Saloon. I had known Glen back in Cowtown, when he and Delbert McClinton were in a band called the Straightjackets. I started making Glen's regular Tuesday night gig in at the Sundance and met a lot of players there. One of the guys that I ran into was singer/songwriter Jerry Williams, another Ft. Worth boy. I had played in a band with him in Dallas while I was going to school at NTSU. Jerry had just signed an album deal with Warner Bros. He asked me to put the horn section together and to write the horn arrangements. I brought in two guys from the Glen Clark band--Lee Thornburg (Wayne Cochran, Tower of Power, Rod Stewart, Supertramp) on trumpet and Greg Smith (Buddy Rich, Jack Mack, Glenn Frye) on bari sax. Jerry had a huge budget to work with and we all made a lot of money. The album was an artistic success, but Warner Bros. refused to promote it, due to conceptual differences between the artist and the label. Making the album helped Jerry Williams out in the long run, though, because Delbert McClinton covered "Givin' It Up For Your Love", a big hit for him, and Bonnie Raitt covered "Talk to Me", which lead to Jerry writing songs for Bonnie's later multi-platinum, Grammy-winning albums.

|

| |

One of the many great players who participated in the Jerry Williams project was yet another Ft. Worth native, Red Young. I had met him when we were both still in high school. Red was putting a band together for a Joan Armatrading world tour, and asked me if I'd be interested in doing it. Although I didn't much like the idea of being away from my family for that long, Beth and I had just bought a house in North Hollywood and it needed a little work, so I saw the tour as an opportunity to get some bread together for home improvements. I also hated to leave the LA scene, just when I was starting to get accepted, but the bread was just too good to turn down, so I said, "Sure, I'm interested." Red brought Joan out to the Sundance to hear me play. She dug my playing, so in January of '79 I was on my way back to Europe--two weeks of rehearsals in London, then a six week European tour. I toured with Joan for most of that year, playing Canada, the U.S., Australia and New Zealand. Joan was a pleasure to work with. Her music was really interesting to play, and she gave her band a lot of freedom to blow. All the players were top-notch--Red on keyboards; Bill Bodine on bass; former Wet Willie band member Rick Hirsch on guitar; Art Rodriquez (Europe), Richie Hayward of Little Feat (Canada and the US), and former Paul McCartney and Wings sideman Denny Seiwell (Australia and New Zealand) on drums; and myself on soprano, alto and tenor saxes. We cut a live album on the Canada-U.S. leg of the tour. I'm really glad that that band got caught on vinyl, because it was great!

|

| |

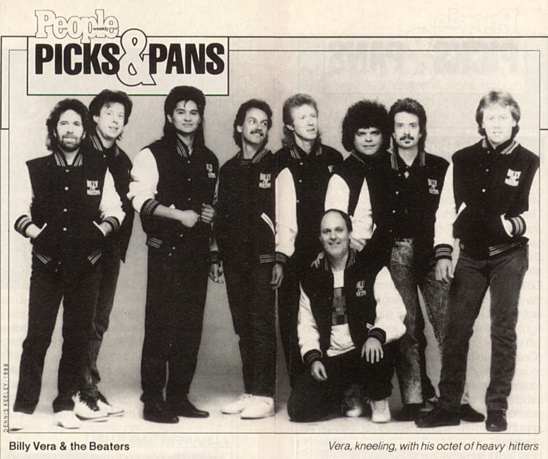

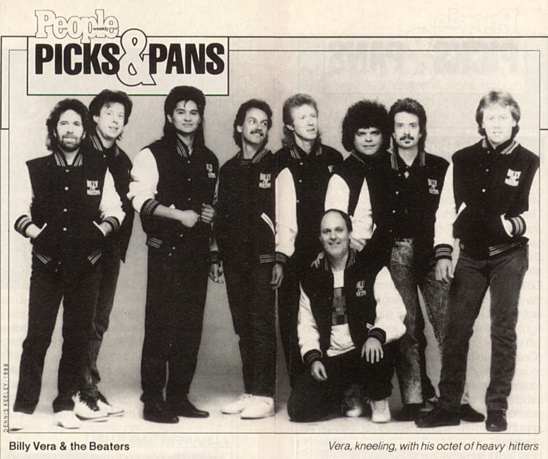

Back in LA towards the end of '79, I was asked to sub for one of the players in a new band that was doing the Monday midnight show at the Troubador in West Hollywood. The band was called Billy Vera and the Beaters, and when the guy that I was subbing for got back to town, Billy decided to keep me on, expanding the horn section from three saxes to four--no brass, just all saxophones, like Fats Domino's band. Soon after I joined the band Billy cut a deal with Alpha Records, a Japanese label that wanted to get into American distribution. We recorded the album live at the Roxy. It was produced by rock guitar legend and former Doobie Brother Jeff Baxter, who had been sitting in with us at the Troub, playing steel guitar, of all things! Early in 1980 we went to Japan to promote the album and to appear at the Tokyo Music Festival, where we won the Gold Prize. The album sold only moderately well in the U.S., and the single, "I Can Take Care of Myself", made it to number 39, just barely breaking into the "top forty". We cut another album later that year in Mussel Shoals, Alabama, produced by the legendary Jerry Wexler. That album really stiffed, and Alpha Records went back to Japan with their tails between their legs. The Beaters are survivors, though. We built up a little circuit of clubs up and down the Southern California coast, from San Diego to Ventura. We were doing pretty well, making a decent living.

|

| |

In '81 I got a call from fellow NTSU alumni Tom Canning, who was Al Jarreau's pianist and musical director. They were working on a new album for Warner Bros., produced by Jay Grayden, and they needed an alto solo on one of the cuts. The album was "This Time" and the tune was "Distracted". When I showed up at the session, which was at Jay's house in the Hollywood Hills, they told me that they'd tried several name players, but they weren't really happy with anything that they'd come up with. Jay said, "You're our last hope, man!" I said, "Thanks for not puttin' on the pressure, man!" I laid the solo down from a spare bedroom. The control room was in the upstairs hall. They liked what I played and the solo made the album. When I later appeared with Al on the "Fridays" TV show, Tom asked me if I could play the same solo. It turns out that Tom Kellock had been playing my solo note-for-note on synth in concerts, and the band was used to hearing it. So I had to go home and transcribe my own solo off the record! I really took it as a complement, though.

|

| |

When Al went back in the studio to do another album, "Breakin' Away", Tom called me again. This time I got two alto solos--"Teach Me Tonight" and "We're In This Love Forever". Jay had me double the solo on "We're In This Love...", giving it a chorus effect. The album was a smash, winning Al a Grammy for best jazz vocalist of the year (I was nominated for a Grammy "MVP" award on saxophone), and "We're In This Love Together" made it to number four on the pop singles chart. My solo on that tune became my signature solo--everyone remembered it and could sing it. People still remember it today, seventeen years later! I began to get calls from some name producers, such as David Foster (Peter Allen's "Bi-Coastal" album) and Maurice White ("Emotion" by Barbra Streisand). I seemed to be well on my way to being a top LA session player. But that was not to be.

|

| |

My wife Beth, who had been working in the bar and restaurant business for over twenty years, was getting tired of working for other people, watching them make all the profits, while she earned a salary and tips. She wanted her own place. I was against it. For one thing, Beth was seven months pregnant with our second child, and for another, I didn't think we had enough money to make a go of it. But she insisted, so we took the equity out of our house and bought the Relic House, a beer and wine bar in Reseda. Two months later our daughter Heather was born. We changed the name of the place to Café Orleans and served cajun and creole cuisine, wine and a large assortment of beers. We booked bands into the place--a lot of local players went through there at one time or another. But not very many customers came through the doors. We were constantly running in the red, and owning a club was also working against my getting work as a musician. Suddenly I was pegged as a club owner. People thought that either I was too busy to play gigs, or that I didn't need the money, being a big-time club owner. About the only playing I did during that time was with Billy and the Beaters. We held onto the place for three dismal years, and then late in '84 we finally threw in the towel. We closed our doors for good and declared bankruptcy.

|

| |

That whole scene put a serious strain on our marriage. Beth finally asked me to leave, and on February 1st, 1985, I moved out. Once again I was devastated. I had lost everything--my family, my house, a lot of money and my credibility as a musician. I turned to alcohol. I had been a heavy drinker for many years, but it had never seriously interfered in my life. But now I was a fullblown alcoholic. I was basically homeless for that entire year, sleeping on one friend's couch until I wore out my welcome, then moving on to the next friend, whoever would offer me a roof over my head. Billy Vera almost fired me for showing up for gigs drunk, which I had never done in the past, but when my replacement wasn't working out, the other horn players lobbied in my behalf and talked Billy into giving me another chance.

|

| |

Right at that time, by some "coincidence", I met Siobhan, who was later to become wife number four. She rescued me, and did I ever need rescuing! Siobhan had won her own bout with alcoholism and helped me to get sober. She and her friend Heidi, who was also sober, were big Beaters fans and had been coming to gigs for at least a year and a half. I'd never even spoken to either of them, though. One night Siobhan stopped me on the way out of the Blue Lagune Saloon, one of the places on our circuit, and told me that she thought that she and I had some mutual friends from New Orleans. It turned out that her sister's boyfriend was in a band with Luther Kent, the singer I had worked with in New Orleans. I walked Siobhan to her car and we talked for hours. After describing to her my drinking habits, I asked her she thought I might be an alcoholic. She said that it just might be a possibility. A week later she asked me to stay with her, in an effort to help me get sober. One thing led to another, and soon Siobhan and I were in a relationship. Three months later I stopped drinking, and I haven't had another drink since January 21, 1986.

|

| |

Meanwhile, Billy talked Rhino Records into releasing a compilation album containing material from the two albums we'd done for Alpha Records. It had been five years since their release and Billy had obtained the right to reissue the material. He told Rhino that they could make their money back through record sales on our gigs alone. Our fans had been bugging us about wanting to buy our records, which were no longer available in the stores. Rhino consented, and the album was called "By Request". Coincidentally, "At This Moment", a ballad from the first album, was played on the two-part season opener of NBC TV's "Family Ties", starring Michael J. Fox. People were calling the network, wanting to know where they could buy the record. Billy convinced Rhino to release the song as a single. Rhino was in the business of releasing compilation albums--they'd never released a single before. "At This Moment" was a four-and-a-half minute ballad recorded live, not the kind of record one would normally think of as single material. But it just took off, and the week of January 21, 1987, the day I celebrated one year of sobriety, "At This Moment" was number one on Billboard Magazine's "Hot One Hundred" singles chart! It was the biggest selling single of that year.

|

|

Now the band began to enjoy a taste of real success. We went on a short tour that summer. We made the talk show circuit, appearing on the Tonight Show several times. Johnny Carson really liked Billy, finding him to be intelligent and articulate with a good sense of humor, at ease in front of the cameras, and an absolute authority on jazz and pop music in the decades between 1940 and 1960. Name a song, and Billy could tell you who had the first hit on it, who produced it, the names of the sidemen on the session, and even the color of the label on the record, as well has what artists had subsequent hits covering the song. Although we appeared on some daytime talk shows, we didn't do any other late-night shows, giving Johnny an exclusive. I think that the strategy paid off, because we were asked to appear on Johnny's New Year's show that year, which was a big thrill for all of us.

|

| |

That year we also appeared on Dick Clark's American Bandstand, the first time for Billy, who told Dick that he used to have a crush on a blond dancer named Frannie Giordano back when the show was based in Philadelphia. I remember having a crush on a dark-haired, mysterious looking girl named Pat Molitari from that same era. We appeared in some other shows produced by Dick Clark, one of which was taped live in the parking lot of Mark C. Bloom's tire store on Sunset, across the street from the Palladium! Man, that's Hollywood!

|

| |

We appeared in the HBO movie "Baha Oklahoma", based on the novel by the same name, written by yet another Ft. Worth native, Dan Jenkins, and starring Leslie Ann Warren. Billy had a part in the film, playing a "Texas Swing" band leader, and we Beaters were used in several scenes as his sidemen. Part of the movie was shot on location in Ft. Worth at a famous country & western bar called Billy Bob's. The opening scene was a big closeup of me playing a tenor solo. My mother, who was at the shooting, was thrilled! She was also thrilled by the fact that Willie Nelson, who had a cameo appearance in the film, was at that shooting. To this day, my mother is still my number one fan!

|

| |

We appeared in another movie--"Blind Date", directed by Blake Edwards and starring Bruce Willis and Kim Bassinger. We had already met Bruce. He had often come to sit in with us on harmonica, at a club in West Hollywood called the Central, while he was doing the "Moonlighting" TV series. But one night Kim showed up at one of our gigs. We were all completely blown away! Blake was a great director and a great guy. We all had a ball working on that film.

|

| |

After the success of "At This Moment" the major labels were hot to sign Billy to do a new album. Al Smith, president of Capitol Records at the time, called Billy personally and said, "Don't sign with anyone till you talk to me." Billy ended up signing with Capitol and we went into the studio to cut the new album, produced by Atlantic Records pioneer Tom Dowd. So there we were in the Capitol Records building on Hollywood and Vine, in Studio A, where Frank Sinatra, Stan Kenton, and hundreds of other big names had recorded their hit albums. And we were working with a producer who had worked with many of the greatest artists in the history of jazz and R 'n B. I was really blown away when Tom told me that he had engineered Coltrane's "My Favorite Things" and "Giant Steps" albums--two of Trane's most important recordings.

|

LP Painting by "L.A. El" (Ellen Bloom)

|

Billy received a star on the Hollywood "Walk of Fame" on the sidewalk right in front of Capitol Records, presented by Al Smith himself. We all thought we were well on our way to becoming a really big-name band. But the album stiffed. In my opinion the material just wasn't as strong as that of the first album we'd done for Alpha. The A & R people at Capitol wanted to find Billy at least one song that they thought would be a sure-fire hit (as if there is such a thing!). Billy refused to do any songs other than those he'd written or co-written with his writing partners, Larry Brown (who penned "Tie a Yellow Ribbon") and Chip Taylor (writer of rock classic "Wild Thang"). Billy's take on it was that his fans wouldn't sit still for his recording other people's material. I think there was a little more to it than that. Billy didn't have THAT many fans, a cult following at best, and mostly local. I think it was more about where the publishing money was going, but I agreed with Billy that recording someone else's material wouldn't have been a good idea. It would have been hard to maintain our identity in the process.

|

| |

After the Capitol album stiffed Billy and the Beaters went back to playing our little Southern California circuit, along with occasional Hollywood parties. Not much happened in the next couple of years, and then we appeared as the house band in a pilot for yet another late-night talk show, called "Into the Night", with radio personality Rick Dees as the host. The show's executive producers were Gallen and Morey, who happened to be Billy's managers at the time. I didn't give the show much of a chance of making it on the air, but the thing got picked up by ABC, and in July of 1990 BIlly and the Beaters were the house band on a five-night-a-week talk show on a major network, with Billy as the musical director.

|

| |

Musicians dream of a cush gig like that one. We'd show up at ABC studios at about 3 pm for rehearsals, break for dinner (catered, of couse) and start taping at 6. By 7:30 we were outta there, which meant we could still play gigs at night. The money was really good, comparable to road money, but of couse we got to stay in town. I got paid extra for writing bumpers and stingers, as well as arrangements for backing up musical guests. I did my own copywork and got paid for that too. That gig was the closest thing to having a "real" job than any that I've ever had in my life. We backed up a wide variety of musical guests, too many to name here, but one that stood out was Henry Mancini. I actually got to play the "Peter Gunn" theme with him, and played the sax solo. It was quite a thrill, because, as I stated earlier, the "Peter Gunn" album was one of the first jazz albums I'd heard.

|

| |

Another guest that was especially memorable for me was country singer Gary Morris, who was starring in "Les Miserables" at the time. On a Friday afternoon I was approached by Billy to write an arrangement of "Bring Him Home", a beautiful solo number that Gary sang in "Les Mis", and that he was scheduled to sing with us on the following Monday. I was given a videotape to work from. When I got home and played the tape I discovered that there was a thirty piece orchestra backing up the singer. I had to try to make Billy and the Beaters sound like a thirty piece orchestra! I spent all weekend on the arrangement, trying different approaches, and finally came up with something that I thought would work. When Gary showed up at rehearsals the following Monday he said, "Oh, I usually just accompany myself on guitar when I do this song on talk shows." My heart sunk. I would have been paid for the arrangement whether we played it or not, but after all the work I put into it I really wanted to get it played. As calmly as I could, I asked him if we could at least try the arrangement I'd written, and he said, "Okay." After a run-through he said, "That'll work fine," and we played it on the show.

|

| |

"Into the Night" was scheduled to run for thirteen weeks, with an option for another thirteen, depending on the ratings numbers. The show struggled in the ratings, but was picked up for another thirteen week run.

|

| |

For the new run ABC brought in a new producer to try and "save" the show, and things started to go sour, fast. Two weeks in, the new producer decided that our band was too old and too white to appeal to the late-night audience. He wanted a younger, more ethnically and sexually mixed band, similar to the house band on the Arsenio Hall Show, which was enjoying excellent ratings at the time. ABC's lawyers found a loophole in our union contract. The contract stated that no player could be replaced during a thirteen week run without being paid for the full thirteen weeks. Dees, along with the new producer, went to Billy and said that due to pressure from the network, they were going to have to cut the size of the band down, getting rid of the horn section. They gave Billy two options: Option number one was that Billy could stay on with the rhythm section and the horns would be fired outright, with no severence pay. They made it clear that Billy and the others would be staying under duress, that they really wanted to replace the whole band, but they'd honor the union contract. Option number two was that they'd pay Billy off for the full thirteen weeks and give the rest of the band two weeks' severence pay, if we all agreed to voluntarily quit. Billy presented the options to the band, with a rep from the Musicians' Union in attendance. The union rep advised us to take option number two, so that everyone would at least get a little money. You can guess how Billy felt about that option. He'd be paid off for the full thirteen weeks and could wash his hands of the whole mess. So we voluntarily quit.

|

| |

The following Monday the backup band was just what Dees and the show's producer said it would be, almost. The players were younger, there was a woman on keyboards, a hispanic guy on percussion and a couple of black guys, on horns! Dees and the show's producer had told us that they did not intend to replace the horns. That was the whole basis of the loophole that got them out of our contract. But now they said that since we voluntarily quit, they were free to hire whomever they wanted to replace us. Well, we were appalled. We went to the Musicians' Union and at first they said that there was nothing they could do about it. But we persisted, and they finally sent lawyers in to meet with the ABC lawyers, arguing that we were unfairly coerced into quitting. The union lawyers reached a settlement with ABC, getting us another three weeks' pay, meaning that we got paid for about half of the second thirteen week run. We band members felt that we really got shafted by everyone concerned. But that's the way it is in this business. If the powers that be decide that they want a change, they'll find a way to do it, regardless of contracts or any other agreements. And there's really no fighting it, because if you do you get labelled as a malcontent, and you end up losing even more work as a result.

|

| |

The Dees show really faltered after that, and they even replaced Rick Dees as host. After a few months ABC dropped the show altogether. But overall doing the show was a good experience for me, as well as for the rest of the band. We got to make really good money in town for a total of seven months. The band got a lot of national exposure, since we were on a major network five nights a week. We got to back up several great singers, and I got some really valuable composing and arranging experience. I was able to really develop my ear, and now transcribing recorded music is a snap for me.

|

Part Four: The LA Years, Continued

|

The next couple of years were really slow. The national exposure Billy and the Beaters had received during the Dees show didn't help us at all, because we had no new album to push and the band was too big to take out on the road without one. Billy wasn't coming up with any new material for the band, so the prospect of doing a new album anytime soon seemed highly unlikely. We fell into a rut of playing the same twenty-five or thirty songs at every gig. The gigs had dwindled considerably, due to the closure of several clubs on our circuit, as well as the stagnation of the band. As I approached the age of fifty, the idea of my doing those same gigs at that age was really a scary thought. I became restless. I felt that I needed to expand my horizons.

|

| |

Over the past few years I had developed an interest in classical or so-called "serious" or "art" music (terms that I don't approve of, because they insinuate that other forms of music aren't either serious or art, which is a ridiculous notion). Siobhan's father is Harry Carmean, a brilliant post-Impressionist artist (a label he probably wouldn't approve of either--labels can really be a drag sometimes). Every time Siobhan and I would go visit Harry he would be listening to classical music while he painted. I had always loved classical music, especially the music of twentieth-century composers such as Stravinsky and Bartok. Because of Harry's influence, I had begun to listen to classical music on a regular basis, and I had been collecting classical albums for the past few years. Now it was practically the only type of music that I listened to. I was also interested in writing film music. I had worked on a "B" movie score a year before and enjoyed it. I had put together a modest midi (musical instrument digital interface) studio with some of the money I'd earned during my stint on the Dees show. I had a keyboard, a few sound modules, and a Mac computer with sequencing and notation software, and a printer, making it possible for me to write music, hear it played back and print out the score and individual parts. I had tried composing "serious" music, but I didn't know enough about it to really do it justice. I needed to study with someone who knew what they were doing.

|

| |

It's amazing to me how certain coincidences have happened throughout my career which changed my life forever. While putting together my midi studio I met a woman named Erica Muhl who was selling a piece of equipment that I needed. I drove out to her house in Valencia to check it out and she and I talked about music for quite a while. I expressed to her an interest in film scoring and that I wanted to study serious composition. She said, "I teach composition at USC." As a teenager Erica had studied in Paris with the world-renowned composition teacher Madame Lilly Boulanger, she had a bachelor's degree from Cal State Northridge, two master's degrees from schools in Italy, and she had just earned her doctor's degree at USC (at the age of thirty-four!) and was now a member of the school's composition faculty. I asked her if she accepted private students outside the school, and she said, "Yes." We set up a meeting at her office on the USC campus, and I showed her some of the music that I had written. She said, "You obviously already know how to write music, so what do you want from me?" I told her that there were several gaps in my knowledge, that I knew next to nothing about writing for strings, and that I really wanted to study composition formally.

|

| |

So I began to study privately with Erica Muhl, either coming to her office at USC, or going out to her house in Valencia. She helped me immensely. We worked on eighteenth century music, the music of Bach. She had me writing canons and fugues, and two and three part inventions. We analyzed the music of Beethoven and Brahms. She had me orchestrate a Ravel piano piece, and then we compared my orchestration to Ravel's. She taught me about writing for strings and showed me some tricks that I could use to make the parts more playable.

|

| |

After I had been studying with Erica for two years, she suggested that I go back to college. She said that I could transfer my credits from NTSU into USC and earn my bachelor's degree in composition. I told her that I doubted that USC would accept me, because of my poor record at NTSU. She said that the composition faculty could intervene in my behalf, if I showed promise. We set up an interview with a panel of composition faculty members. I showed them the work that I had done while studying with Erica. I had written a brass quintet, a solo cello piece and a solo piano piece, which I had just finished orchestrating for full orchestra. Based on that interview they accepted me, gave me a partial scholorship and placed me at the junior level in composition, and at the senior level in orchestration.

|

| |

That summer, after living together for seven years, Siobhan and I were married, her first and my fourth (and hopefully last!). We were living on Lookout Mountain in the Hollywood Hills, in the house where Siobhan had been raised, and which she had bought from her father. Lookout Mountain is a very artistic neighborhood. Several artists, musicians and actors live in the area. Our next door neighbors were Cheryl Bentyne of Manhattan Transfer on one side, and Mark Volman of the Turtles on the other. David Alan Grier of "In Living Color" lived across the street from us, and actor James Spader lived three doors down.

|

| |

In the fall of '92 I enrolled at USC (twenty-three years after leaving NTSU), majoring in composition, with a concentration in film scoring. Once again my grades improved drastically upon returning to school. During my three years at USC my GPA was 3.85, and I never earned a grade lower than a B+. It was a wonderful experience for me. I studied composition with Dr. Steven Hartke, former winner of the Prix de Rome and a Fulbright Fellowship in Brazil, as well as many other honors. My orchestration instructor was Dr. Donald Crockett, former composer in residence with the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra. I also studied with Dr. Frank Ticheli, whose music appeared on a cd with the music of John Corigliano. I also studied with nationally recognized composer Richard Danialpore during his one-week residency at USC.

|

| |

Soon after my enrollment at USC I received a call from trumpeter Lee Thornburg, my good friend from the Sundance Saloon days. He was putting a horn section together for a tour of France with Véronique Sanson, a French singer who had at one time been married to Steven Stills. Lee asked if I would be interested. The tour was scheduled for six weeks, beginning in early March, right in the middle of the spring semester. I went to my instructors and asked them how they felt about my missing six weeks of school, and they said that it was okay with them, as long as I got my work done. I had an orchestration project that was due for a reading by the USC Symphony two days after I got back, so I bought a Powerbook computer, turned the score in before I left, and worked on the individual parts while I was out on the road.

|

| |

Working with Véro was great! She's a great singer, as well as an accomplished pianist. Her music is very sophisticated and extrmemely interesting, with many stylistic influences, including classical, jazz, rock and world music. In addition to that she's a very sweet lady. She's undoubtedly the nicest and most laid-back artist I've ever perfomed with. It was a real thrill to get to go back to France, this time touring the entire country, going to practically every major city. The architecture and the art galleries were of particular interest to me. In Paris I visited the Louvre, Musée d'Orsay (Impressionist art and Art Nouveau furniture), l'Orangerie (Impressionist art, including Monet's "Water Lilies"), the Picasso Museum and the Salvidor Dali Museum. I must have visited a hundred breathtakingly beautiful cathedrals. Every city in France has at least one.

|

| |

In the spring of '94 I went back to France for another six week tour with Véro. While I was there I got a call from Manhattan Transfer to do a week at the MGM Grand Hotel in Las Vegas. I had met Tim Hauser through Billy Vera, and of course Cheryl Bentyne was my next door neighbor. I had also played a solo for them on the song "Choo-Choo Cha Boogie" for the sountrack to the movie "A League of Their Own." I was really excited to be playing with Manhattan Transfer. I had always enjoyed their music, and it was a chance for me to play jazz and get paid well for it. Playing with them was a great experience for me. After the Vegas gig The Transfer asked me to do a summer tour. We played the "sheds" and dinner theaters on the East Coast and in the Midwest, such as Wolf Trap, Interlocken, the Westbury Music Fair and Tanglewood. We played the Newport Jazz Festival, where we were headliners over Wynton Marsalis! I was scheduled to go back to France with Véro, but as luck would have it, the Transfer was taking a break during the time that I was needed in France, so after playing the Montreal Jazz Festival with the Transfer I flew straight to Paris for a five week tour with Véro. After that tour ended I flew from Paris to Columbus, Ohio, to finish the tour with the Transfer.

|

| |

I got back to LA just in time for late registration for the fall semester of '94 at USC. I decided to change my major to composition, with no concentration in film scoring. I couldn't take the film scoring courses part-time, and I couldn't go to school full-time, because I also had to make a living. Film scoring also seemed like a worse rat race than being a player, and besides, I was becoming more and more interested in serious composition.

|

| |

The general education courses that I chose to take while attending USC were also important in my development. I think that it is important for a musician to have an understanding of the other arts, and how the work of artists in other fields also relates to music. USC has a wide variety of general ed courses from which to chose, and the ones that I picked were interesting, challenging and thought-provoking. I studied "The History of Philosophy in the Modern World," studing the philosophy of Descarte, Berkley and Hume. I studied an Art History course, covering the beginnings of Impressionism in the 1860s through Surrealism in the 1930s. I also studied twentieth century French Literature in english translation, reading works by Proust, Sartre and Camus, among others. I began to see how the work of the Impressionist painters, such as Monet and Degas, related to that of "Impressionist" composers, such as Ravel and Debussy. I saw how the "pointalism" of the artist Paul Serault related to the "pointalism" of composer Anton Webern, and also how the two differed. I also developed an interest in the tremendous impact that the Industrial Revolution had on philosophy, art, literature and music.

|

| |

That year Siobhan and I began to have marital problems. The amount of time that I was spending on my schoolwork, as well as the time that I was spending out of the country, was really beginning to bother Siobhan. I think that there was a jealosy factor in the situation as well. Siobhan had always wanted to be a singer, and she had attended the Dick Grove School of Music, studying vocal performance and songwriting. She had learned quite a lot, and was performing regularly in a club in our neighborhood, called the Coconut Teazer. It was sort of an open mike situation, but a friend of ours had been "discovered" there. When I could, I'd make the gig with Siobhan. But I was getting all these great gigs, touring and recording with big-name artists, and I think that she was jealous. And because of my commitment to USC, as well as the travelling, I wasn't always available for her needs. I tried really hard this time to try and work out our marriage. We went to counciling, but it didn't seem to help. In the summer of '95 we separated.

|

| |

The separation was extremely difficult for me. When my previous marriages had broken up I was able to anesthetize my feelings with alcohol. But I was sober now. I was awake for this one, and I took it really hard. I discovered that the reason I had always gone directly from one relationship into another was that I was terrified of being alone. I had never been alone for any significant length of time in my life. I'd never looked for an apartment by myself. I'd never dealt with getting the electricity and phone turned on, finding furniture, etc., and the idea of doing these things all by myself scared me to death--and I was forty-nine years old! Obviously I needed to face my fears. Of course I was able to do all of those things, and in fact I really enjoyed it, especially decorating my own apartment. Through a friend I had found an apartment in Hollywood, near Beachwood Canyon (another artistic community). I accomplished the task of decorating it, tastefully and economically. And I didn't have one thing in my apartment that was frilly or the color pink!

|

| |

At first I was terribly lonely and I missed Siobhan desparately. But I knew that I had to give her space, and I didn't want to end up stalking my own wife. So of course I began to work on finding her replacement. But luckily I was able to see the error in that move, which would have been following the pattern of my entire adult life. So I learned to enjoy living alone.

|

| |